Anatomy of Industrial Valves

Controlling the flow of liquid, gas and sometimes solids, valves have a deceptively simple job. Like an on/off (or dimmer) switch for tangibles, every valve is designed and built to guide the movement of a specific material.

Industrial valves are used in thousands of products and systems, from water infrastructure to offshore oil rigs. Since they have such a wide variety of applications, it naturally follows that valves come in thousands, if not millions, of shapes and sizes. They also run the gamut from simple to highly complex.

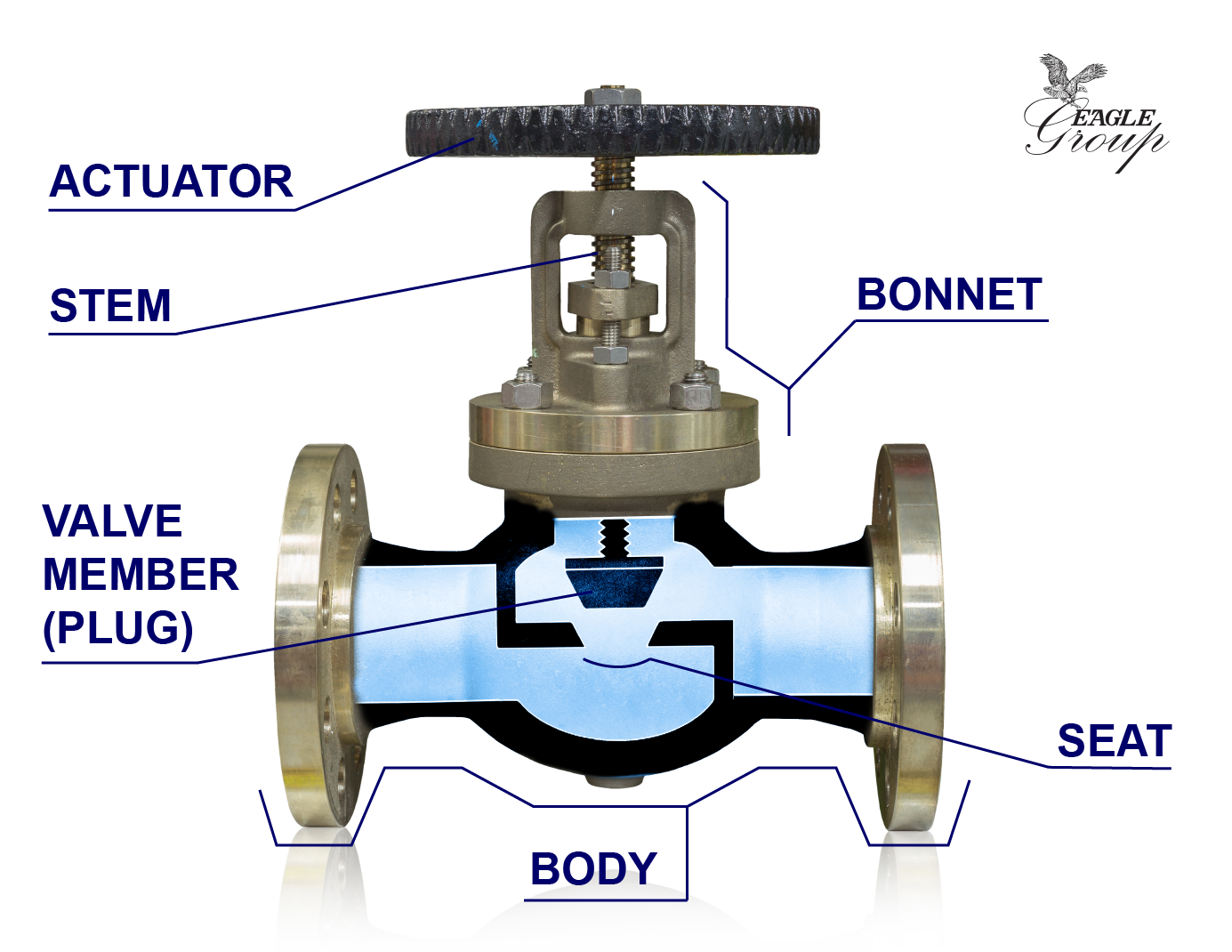

Despite high levels of variation, most industrial valves can be broken down into the same basic components: body (or enclosure), bonnet, actuator, valve member and seat.

Valve Body

The body, or enclosure, of the valve is often the largest component. Material flows through the body between the ports, and all other valve components connect to it. For example, a standard gate valve has three holes: the upstream port, where material flows into the body; the downstream port, where material leaves the body, and another hole on top to connect the bonnet and actuator. Of course, many valves have three or more ports as well, but the basic configuration is similar.

Depending on the type, size and complexity of the valve, valve bodies may be comprised of a single piece or be fabricated from several separate pieces. Modern casting processes that make use of cores allow the addition of complex inner cavities. These processes, including shell mold casting, investment casting and permanent mold casting, are often used for casting valves.

Depending on the type, size and complexity of the valve, valve bodies may be comprised of a single piece or be fabricated from several separate pieces. Modern casting processes that make use of cores allow the addition of complex inner cavities. These processes, including shell mold casting, investment casting and permanent mold casting, are often used for casting valves.

Valve Bonnet

The valve bonnet isn't necessary for every valve, but most standard industrial valves include this component. The bonnet attaches to the top of the valve body using either threads inside the valve body or bolts attached to flanges on both the body and the bonnet. The internal characteristics of the bonnet allow additional components to be attached, like the actuator and the valve member.

The bonnet often remains stationary while the valve is in use, but can be removed to service internal valve parts or to clear the body of obstructions. In some cases, the bonnet is combined with the body as a single part. Even if they are separate parts, the bonnet is often considered a characteristic of the overall enclosure. Without it, the material flowing through the valve would leak, and it would be impossible to actuate the valve.

Valve Actuator

Actuators are, in a way, the most important valve component. They provide the ability to control flow; without that ability, a valve is only a channel or a container. Actuators can be as simple as a hand wheel or a handle, or as complex as a computerized, automated valve controller.

In a traditional globe valve, the operator turns the hand wheel at the top of the valve, and the actuator moves a stem up and down along a threaded channel within the bonnet. As the stem moves up, it frees the valve member from the funnel-shaped seat and allows material to flow through the valve body.

Valve Member

The valve member is the component that directly prevents material from flowing through the body. Depending on the type of valve, the valve member can take on many shapes. Globe valves often utilize a disc-shaped valve member with tapered sides, or even a ball-shaped valve member that tightens against a funnel-shaped seat. Ball valves are so named because they use spherical valve members, cut so that they allow flow when the valve is open. Butterfly valves use disc-shaped valve members that rotate to allow or obstruct flow.

Valve Seat

The seat is a characteristic of the valve body that acts as a counterpart to the valve member. When a valve is sealed shut, the valve member and seat should be in full contact, and the connection should be tight enough so that no material can pass through. In a globe valve, the seat matches the sides of the tapered, disc-shaped valve member so that when the two components meet they form a seal. Similarly in butterfly valves, the seats are built into the valve bodies and allow a seal to form when the valve members are in full contact. In many cases, valve seats are coated with rubber or teflon to allow a tight seal to form.

Learn more about control valve trim on the Kimray Blog.

Manufacturing Industrial Valves

Since valves are made up of a number of different parts, they cannot be manufactured using a single process. Metal casting is the method of choice to produce most valve components, but they nearly always need to be machined before they are finished.

In order to provide the greatest strength and sealing ability, valve bodies can be cast as single parts by using both molds and cores. Shell molding, investment casting and greensand casting all make it relatively easy to produce hollow parts with complex inner cavities. Because of this property, these three processes are often used for casting valves.

After casting valve parts, the next step is to use CNC machining to finish the parts. Ports–where material enters and exits the valve body–can be threaded to allow the valve to attach to pipes on both sides. The interface between the valve body and the valve bonnet is also often threaded, allowing the two parts to be connected and separated for maintenance. Depending on the valve mechanism, actuators may be produced using more machining than casting. The threaded stem between the actuator and the valve member in gate valves can sometimes be machined entirely from bar stock. If valve members are not entirely machined, they almost always require some machining to ensure a precise fit. Similarly, while the basic shape of the seat can be included in the valve body casting, it must also be machined to ensure a snug fit with the valve member.

For more information on casting valves and machining valve components, check out our "Valve Types and Applications" post.

Tags: Valves, Valve Casting

Written by Jim Smith, Jr.

Jim Smith, Jr. is the Technical & Sales Manager at Eagle Aluminum Cast Products in Muskegon, MI. Given his father’s career as a mechanical engineer, Jim grew up in foundries and often used castings his father brought home as toys. During his college years and into his first jobs, Jim developed skills in quality, engineering and customer service. Jim joined Eagle Aluminum in 2012 as a Technical Analyst and now manages all of the company’s Technical and Sales functions.